Physioelectrochemical Investigation of Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Saccharose on Conductive Polymer Modified Graphite Electrode

Article information

Abstract

In this study we investigated the electrocatalytic oxidation of saccharose on conductive polymer- Nickel oxide modified graphite electrodes based on the ability of anionic surfactants to form micelles in aqueous media. This NiO modified electrode showed higher electrocatalytic activity than Ni rode electrode in electrocatalytic oxidation of saccharose. The anodic peak currents show linear dependency with the square root of scan rate. This behavior is the characteristic of a diffusion controlled process. Under the CA regime the reaction followed a Cottrellian behavior and the diffusion coefficient of saccharose was found in agreement with the values obtained from CV measurements.

1. Introduction

Electrocatalytic processes involving the oxidation of sugars are of great interest in many areas, ranging from medical applications to waste water treatment and from the construction of biological fuel cells to analytical applications in the food industry [1-3]. On the other hand, the electrochemical detection of carbohydrates are important in many areas [4]. The investigation of glucose electrochemical oxidation began in 1960s, and has remained a very active research area [5]. Bagotzky and Vassilyev [6] first reported the electro-oxidation behavior of glucose in an acidic medium. At about the same time, Bockris et al. [7] studied this reaction at high temperature in alkaline solutions. Considerable attention has been directed to the use of biofuel cells on account of their mild operating conditions and diverse applications [8]. Biofuel cell systems utilize biocatalysts such as enzymes and microorganisms as the electrocatalyst instead of transition metal catalysts that are utilized in the conventional fuel cell systems. Several organic compounds and especially biomass based compounds such as sugars and alcohols can be utilized in biofuel cells and in principle highly efficient energy conversion can be achieved compared to the transition metal-based fuel cells [9]. Different metal electrodes, Ni [10-12], Au [13], Pt[14] and Cu [15] provide simple way for the catalytic oxidation of carbohydrates at constant applied potentials. On Ni- and Cu-electrodes, compared to Pt- and Au-electrodes, the reaction is greatly enhanced as a result of their catalytic effect [16,17]. Previous studies provided evidence of a reaction mechanism involving electron transfer mediated by a surface-bound Ni2+/Ni3+ (or Cu2+/Cu3+) redox couple [16,17].

Conducting electroactive polymers are novel materials which are either being successfully used or expected to find use in various fields of many technological applications [18]. Among many applications of conducting polymers, electrochemical sensor applications seem to be very promising. Electrodes, modified with conducting polymers, possess many interesting features that can be exploited for numerous electroanalytical and sensor applications. Particularly, elucidating the bioelectrochemistry and electroanalysis of biologically important substances, are under intense research with the use of chemically modified electrodes. Several conducting polymers, such as polypyrrole (PPy), polyaniline (PANI), polythiophene (PTH) and poly ortho amino phenol (POAP), have been already in extensive use in order to immobilize desired chemical species and enzymes for development of sensors [19-23].

Moreover, the possibility of dispersing metallic particles inside the polymers gives electrodes with higher surface areas, enhanced electrocatalytic activities and facilitates electron transfer due to semi conducting properties [24-28] and change in fermi level toward the oxidation of organic molecules [29]. Organic-inorganic composite have attracted consid-erable attention as they can combine the advantages of both components and may offer special through reinforcing or modifying each other [30]. Electrodeposition is an effective way to make composite films with a large variety of tunable parameters and so has the advantage of convenient film control.

The purpose of the present work is to study the electrochemical oxidation of saccharose on a G/POAP-NiO film in a solution of 1 M NaOH aiming at the elucidation of the mechanism, derivation of the kinetic parameters of the process and the usefulness of the electrocatalytic process.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Ortho amino phenol (OAP), Sodium hydroxide, lithium perchlorate, nickel nitrate, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and saccharose used in this work were Merck product of analytical grade and were used without further purification. Doubly distilled water and pyrrole was used throughout.

2.2. Apparatus

Electrochemical studies were carried out in a conventional three electrode cell powered by an electrochemical system comprising of EG&G model 273 potentiostat/galvanostat and Solartron model 1255 frequency response analyzer. The system is run by a PC through M270 commercial software via a GPIB interface. Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE), a Pt wire and a graphite (G) electrode were used as the reference, counter and working electrodes, respectively. All studies were carried out at 298 ± 2 K.

2.3. Preparation of NiO-POAP electrodes via electrodeposition

Films of POAP were formed on the graphite surface using an OAP monomer solution (0.01 M OAP in 0.1 M LiClO4 and 0.1 M HClO4) and (0.01 M OAP in 0.1 M LiClO4, 0.1 M HClO4 and 0.005 M SDS). The electropolymerization was carried out by potential cycling (40 cycles at a scan rate of 50 mV/s between -0.2 and 0.9 V versus SCE. In order to incorporate Ni (II) ions into the POAP film, the freshly electropolymerised graphite electrode was placed at open circuit in a well stirred aqueous solution of 0.1 mol L−1 Ni (NO3)2. Nickel was accumulated by complex formation between Ni (II) in solution and amines sites in the polymer backbone [31,32] in a given period of time. The polarization behavior was examined in 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH for G/POAP-NiO using cyclic voltammetry. This technique allows the oxide film formation in parallel with inspecting the electrochemical reactivity of the surface. Voltammograms were recorded by cycling the potential between 0.1 and 0.8 V at 100 mV s−1 until a stable voltammogram was obtained. A mixture of NiO2 and NiO-OH may coexist in the films displayed characteristic NiOx electroactivities as previously reported for nickel oxides [25].

3. Results and discussion

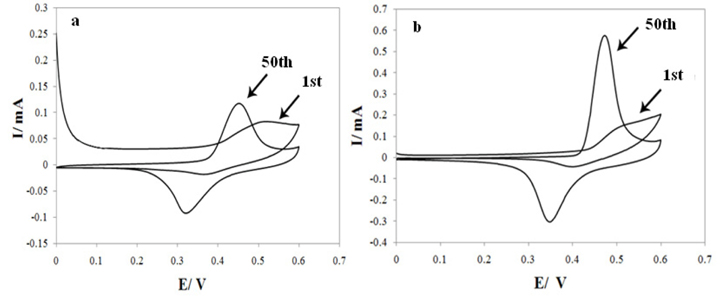

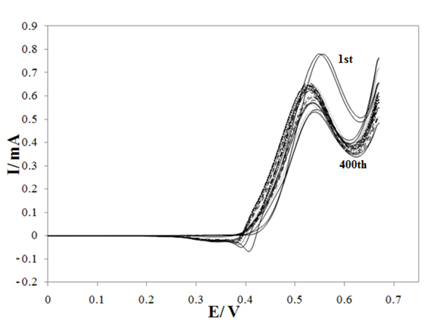

Figs. 1a, b presents cyclic voltammogram (CV) of a G/Ni- POAP and G/ Ni-SDS-POAP electrode in 0.1 M NaOH solution recorded at a potential sweep rate of 100 mV s−1. In the sweep a pair of redox peaks is assigned to Ni2+/ Ni3+ redox couple in alkaline media. The larger Ni response at the G/Ni-SDS-POAP respect G/Ni- POAP electrode is proposed to be the SDS enhances the catalytic properties of nickel oxide through fine dispersion of the catalyst particles into the conductive polymer matrix to results in a drastic increase in surface area.

Consecutive cyclic voltammogram of G/Ni-POAP (a) and G/Ni-SDS-POAP (b) electrodes in 0.1 M NaOH at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1.

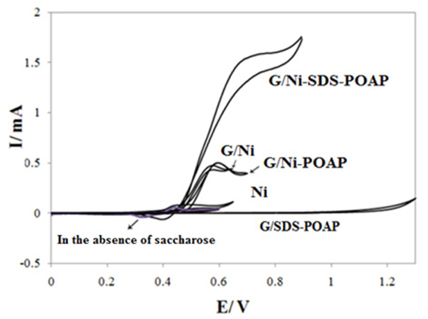

Fig. 2a shows cyclic voltammograms of G/Ni-SDS-POAP and other electrodes in 0.1 M NaOH solution in the absence and presence of 0.003 M saccharose at a potential sweep rate of 10 mV s−1. As can be seen in 0.003 M saccharose G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrode generates higher current density for electro-oxidation in NaOH solution. The histograms of these behavior and difference between different electrodes response are presented in Fig. 2b. The larger saccharose response at the G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrode is due to the composite material which enhances the catalytic properties of nickel oxide through fine dispersion of the catalyst particles into the conductive polymer matrix to results in a drastic increase in surface area. The electrocatalytic behavior of any material depends on various factors such as: (i) the position of the energy levels of the reactive species and the electrode material; (ii) the charge-transfer process across the electrode/electrolyte interface; (iii) the diffusion of the reactants into/near the electrode surface; and the surface morphology of the electrode. These results may be explained on the basis of electrochemical reactions at a semiconductor electrode. Here, POAP is considered as a p-type semiconductor. The impurity doping level will be situated above the uppermost valence level since POAP is a p-type material. Since the electrode is in an anodic condition, electrons are abstracted from the electrolyte and these combine with holes in the semiconductor. In the present study, it is therefore clear that charge transfer at the electrode/electrolyte interface has the most influence on the electro-oxidation of saccharose when using a semi-conducting polymer electrode. It should also be noted that such charge transfer processes are also important in electrochromism and photo-electrochemical effects. In the first step of charge transport within POAP films, which are considered to be p-type semiconductors where holes are majority carriers, there are two processes of importance, inter chain and intra chain transport. The intra chain transport of charge takes place along the main chain, which is facilitated due to extended conjugation. The inter chain charge transport occurs mainly across one chain to the other by hopping mechanism.

cyclic voltammograms of G/Ni-SDS-POAP and other electrodes in 0.1 M NaOH solution in the absence and presence of 0.003 M saccharose at a potential sweep rate of 10 mV s−1.

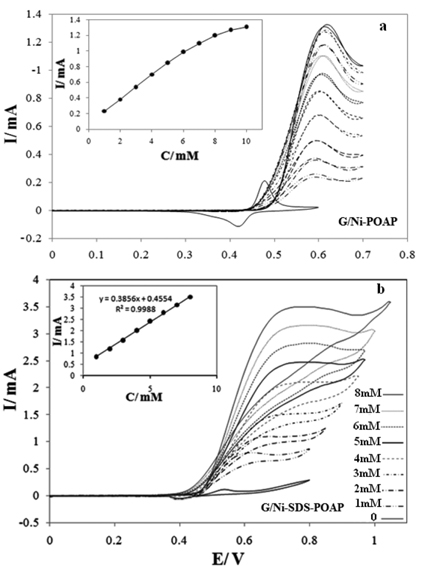

Figs. 3a, b show cyclic voltammograms of G/Ni-POAP and G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrodes in the 0.1 M NaOH solution in the presence of various concentrations of saccharose at a potential sweep rate of 10 mV s−1. At G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrodes, oxidation of saccharose appeared as a typical electrocatalytic response. The anodic charge increased with respect to that observed for the modified surface in the absence of saccharose and it was followed by decreasing the cathodic charge upon increasing the concentration of saccharose in solution. In the presence of 0.003 M saccharose with the potential sweep rate of 10 mV s−1, the ratio of anodic to cathodic charge in the presence of saccharose was 89/8 while in its absence it was 72/63. Charge is obtained by integrating the anodic and cathodic peaks after background correction.

cyclic voltammograms of G/Ni-POAP (a) and G/NiSDS-POAP (b) electrodes in the 0.1 M NaOH solution in the presence of various concentrations of saccharose at a potential sweep rate of 10 mV s−1.

The anodic current in the positive sweep was proportional to the bulk concentration of saccharose (Fig. 3b inset) and any increase in the concentration of saccharose caused an almost proportional linear enhancement of the anodic current. So, catalytic electrooxidation of saccharose on G/Ni-SDS-POAP seems to be certain.

The decreased cathodic current that ensued the oxidation process in the reverse cycle indicates that the rate determining step certainly involves saccharose and that it is incapable of reducing the entire high valent nickel species formed in the oxidation cycle. The electrocatalytic oxidation of saccharose occurs not only in the anodic but also continues in the initial stage of the cathodic half cycle. Saccharose molecules adsorbed on the surface are oxidized at higher potentials parallel to the oxidation of Ni(II) to Ni(III) species. The later process has the consequence of decreasing the number of sites for saccharose adsorption that along with the poisoning effect of the products or intermediates of the reaction tends to decrease the overall rate of saccharose oxidation. Thus, the anodic current passes through a maximum as the potential is anodically swept. In the reverse half cycle, the oxidation continues and its corresponding current goes through the maximum due to the regeneration of active sites for adsorption of saccharose as a result of the removal of adsorbed intermediates and products. Surely, the rate of saccharose oxidation as signified by the anodic current in the cathodic half cycle drops as the unfavorable cathodic potentials are approached.

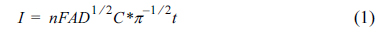

Fig. 4 shows the cyclic voltammograms of G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrode in 0.1 M NaOH in presence of 0.001 M saccharose at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 for 400 cycles. It is observed that the current density of electro-oxidation of saccharose is almost constant in 400cycles due to the stability of electrocatalyst in this cycle number and indicating that saccharose reacted with the surface and no poisoning effect on the surface was observed.

Repeated cyclic voltammograms of 0.001 M saccharose oxidation on G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrode at 10 mV s−1, cycle number: 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 400.

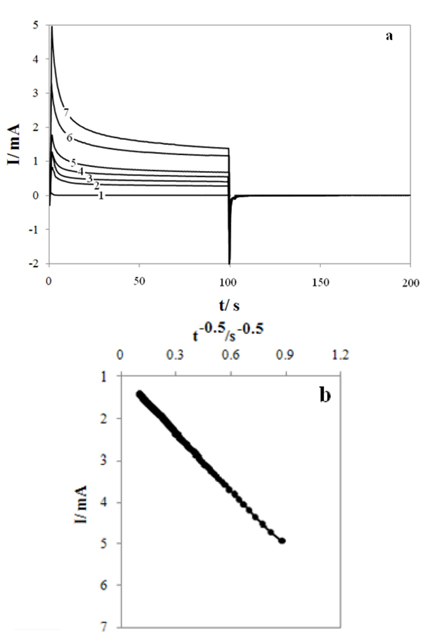

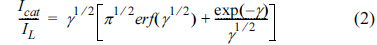

Chronoamperograms were recorded by setting the working electrode potentials to the desired values and measuring the catalytic rate constant on the G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrode surface. Fig. 5a presents chronoamperogram for the G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrode in the absence and presence of saccharose over the concentration range 0.0 - 0.006M. The applied potential step was 540 mV. Plotting the net currents versus the minus square roots of time results in linear dependencies (Fig. 5b). Therefore, a diffusion-controlled process is dominant for electrooxidation of drugs. By using the slopes of these lines, we can obtain the diffusion coefficients of the drugs according to the Cottrell equation [33]:

where D is the diffusion coefficient, and C* is the bulk concentration. The mean values of the diffusion coefficients for saccharose were 4.26×10−6 cm2 s on the G/Ni-SDS-POAP surface. Chronoamperometry can also be used to evaluate the catalytic rate constant according to [33].

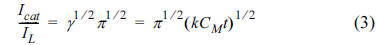

where Icat and IL are the currents in the presence and absence of the saccharose, respectively, and γ = k0Ct is the argument of the error function. k0 is the catalytic rate constant, and t is elapsed time. In cases where γ > 1.5, erf(γ 1/2) is almost equal to unity, and Eq. (2) can be reduced

From the slopes of the Icat/IL versus t1/2 plots, the mean values of k0 obtained for saccharose were 7.86 × 104 cm3 mol−1 s−1and 7.24 × 104 cm3 mol−1 s−1 in the surface of G/Ni-SDS-POAP and G/Ni-POAP electrodes respectively.

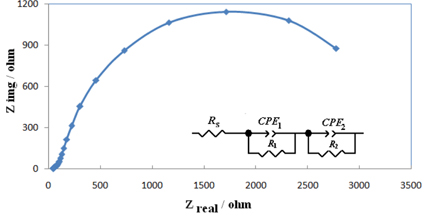

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy is one of the best techniques for analyzing the properties of conducting polymer electrodes and charge transfer mechanism in the electrolyte/electrode interface. It has been broadly discussed in the literature using a variety of theoretical models. Fig. 6 shows the Nyquist diagrams of G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrodes recorded at the oxidation peak potential of saccharose as dc-offset. Diagrams of G/Ni-SDS-POAP consist of a small semicircle terminated to depressed capacitive semicircles at low frequency end of the spectrum. The equivalent circuit compatible with the Nyquist diagram recorded in the presence of saccharose was depicted in Fig. 6. To obtain a satisfactory impedance simulation of methanol electro-oxidation, it is necessary to replace the capacitor C with a constant phase element (CPE) in the equivalent circuit [34-46]. The most widely accepted explanation for the presence of CPE behavior and depressed semicircles on solid electrodes is microscopic roughness, causing an inhomogeneous distribution in the solution resistance as well as in the double-layer capacitance. The parallel combination of charge transfer resistance R1 and constant phase element CPE1 accounts for the injection of electrons from the conductive polymer to the back metallic contact. R2 and CPE2 represent the saccharose oxidation.

Nyquist diagrams of G/Ni-SDS-POAP electrodes recorded at the saccharose oxidation peak potential as dcoffset for 0.001 M saccharose.

A number of mechanisms have been proposed for the electro- oxidation of alcohols on Ni in alkaline solutions. While Fleischmann et al. [33] assumed catalytic/intermediate role for NiOOH in the course of an anodic potential sweep.

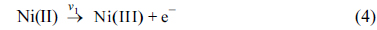

On the basis of our study and consistent with the literature [28, 33, 47, 48] the following mechanism is proposed for the mediated electro-oxidation of saccharose on G/Ni-SDS-POAP and the corresponding kinetics is formulated. The redox transition of nickel species present in the film is

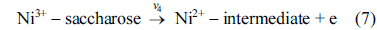

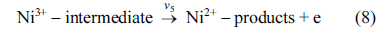

and saccharose is oxidized on the modified surface via the following reaction

where Ni3+ sites are regenerated by the power source and on the Ni3+ oxide surface by direct electro-oxidation

Eqs. (5) and (6) are according to Fleischmann mechanism and in Eqs. (7) and (8), Ni3+ used as active surface for saccharose oxidation.

4. Conclusion

POAP was formed by cyclic voltammetry in monomer solution containing sodium dodesyl sulfate (SDS), on graphite (G) electrode surface. Then, Ni(II) ions were incorporated to electrode by immersion of the polymeric modified electrode having amine group in Ni(II) ion solution. The morphologies and elemental components of the film were inspected by scanning electron microscopy and EDS respectively. The nickel oxide film was tested for electro-oxidation of saccharose in alkaline media. The modified electrodes showed electrocatalytic activity for the oxidation of saccharose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to the Iranian Nano Council for supporting this work.

References

D.C. Johnson, W.R. LaCourse, Carbohydrate Analysis, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam (1995).

Johnson D.C., LaCourse W.R.. Carbohydrate Analysis Elsevier Science. Amsterdam: 1995.E. Katz, I. Willner, A.B. Kotlyar, J. Electroanal. Chem. 479, 64(1999).

Katz E., Willner I., Kotlyar A.B.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999;479:64. 10.1016/S0022-0728(99)00425-8.S.B. Khoo, M.G.S. Yap, Y.L. Huang, S.X. Guo, Anal. Chim. Acta, 351, 1331(1997).

Khoo S.B., Yap M.G.S., Huang Y.L., Guo S.X.. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1997;351:1331.D.C. Johnson, S.G. Weber, A.M. Bond, R.M. Wightman, R.E. Shoup, I.S. Krull, Anal. Chim. Acta, 180, 187(1986).

Johnson D.C., Weber S.G., Bond A.M., Wightman R.M., Shoup R.E., Krull I.S.. Anal. Chim. Acta 1986;180:187. 10.1016/0003-2670(86)80007-1.H.W. Lei, B.L. Wu, C.S. Cha, H. Kita, J. Electroanal. Chem. 382, 103(1995).

Lei H.W., Wu B.L., Cha C.S., Kita H.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1995;382:103. 10.1016/0022-0728(94)03673-Q.V.S. Bagotzky, Yu.B. Vassilyev, Electrochim. Acta, 9, 1329(1964).

Bagotzky V.S., Vassilyev Yu.B.. Electrochim. Acta 1964;9:1329. 10.1016/0013-4686(64)87009-2.J.O’M. Bockris, B.J. Piersma, E. Gileadi, Electrochim. Acta, 9, 1329(1964).

Bockris J.O’M., Piersma B.J., Gileadi E.. Electrochim. Acta 1964;9:1329. 10.1016/0013-4686(64)87009-2.T. Ikeda, K. Kano, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1647, 121(2003).

Ikeda T., Kano K.. Biophys. Acta 2003;1647:121.R.A. Bullen, T.C. Arnot, J.B. Lakeman, F.C. Walsh, Biosens. Bioelectron. 21, 2015(2006).

Bullen R.A., Arnot T.C., Lakeman J.B., Walsh F.C.. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006;21:2015. 10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.030.C. Zhao, C. Shao, M. Li, K. Jiao, Talanta, 71, 1773(2007).

Zhao C., Shao C., Li M., Jiao K.. Talanta 2007;71:1773.M. Morita, O. Niwa, S. Tou, N. Watanabe, J. Chromatogr. A. 837, 17(1999).

Morita M., Niwa O., Tou S., Watanabe N.. J. Chromatogr. A 1999;837:17. 10.1016/S0021-9673(99)00047-3.M. Fleischmann, K. Korinek, D. Pletcher, J. Electroanal. Chem. 31, 39(1971).

Fleischmann M., Korinek K., Pletcher D.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1971;31:39. 10.1016/S0022-0728(71)80040-2.A. Hilmi, J.H.T. Luong, Anal. Chem. 72, 4677(2000).

Hilmi A., Luong J.H.T.. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:4677. 10.1021/ac000524h.E. Skou, Electrochim. Acta. 22, 313(1977).

Skou E.. Electrochim. Acta. 1977;22:313. 10.1016/0013-4686(77)85079-2.L.A. Colon, R. Dadoo, R.N. Zare, Anal. Chem. 65, 476(1993).

Colon L.A., Dadoo R., Zare R.N.. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:476. 10.1021/ac00052a027.M. Fleischmann, K. Korinek, D. Pletcher, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1396(1972).

Fleischmann M., Korinek K., Pletcher D.. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1972;2:1396.P.F.F. Luo, T. Kuwana, Anal. Chem. 66, 2775(1994).

Luo P.F.F., Kuwana T.. Anal. Chem. 1994;66:2775. 10.1021/ac00089a028.V. Singh, S.Mohan, G. Singh, P.C. Pandey, R. Prakash, Sens. Actuators B, 132, 99(2008).

Singh V., Mohan S., Singh G., Pandey P.C., Prakash R.. Sens. Actuators B 2008;132:99. 10.1016/j.snb.2008.01.007.S. Mokrane, L. Makhloufi, H. Hammache, B. Saidani, J. Solid State Electrochem. 5, 339(2001).

Mokrane S., Makhloufi L., Hammache H., Saidani B.. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2001;5:339. 10.1007/s100080000161.D.N. Upadhyay, D.M. Kolb, J. Electroanal. Chem. 358, 317(1993).

Upadhyay D.N., Kolb D.M.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1993;358:317. 10.1016/0022-0728(93)80447-P.J. Chen, C.O. Too, G.G. Wallace, G.F. Swiegers, B.W. Skelton, A.H. White, Electrochim. Acta, 47, 27(2002).

Chen J., Too C.O., Wallace G.G., Swiegers G.F., Skelton B.W., White A.H.. Electrochim. Acta 2002;47:27.P.C. Pandey, S. Upadhyay, G. Singh, Rajiv Prakash, R.C. Srivastava, P.K. Seth, Electroanalysis, 12, 517(2000).

Pandey P.C., Upadhyay S., Singh G., Prakash Rajiv, Srivastava R.C., Seth P.K.. Electroanalysis 2000;12:517. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4109(200005)12:7<517::AID-ELAN517>3.0.CO;2-Y.R.M. Banik, Mayank, R. Prakash, S.N. Upadhyay, Sens. Actuators B, 131, 295(2008).

Banik R.M., Prakash Mayank, R., Upadhyay S.N.. Sens. Actuators B 2008;131:295. 10.1016/j.snb.2007.11.022.M.G. Mahjani, A. Ehsani, M. Jafarian, Synth. Met. 160, 1252(2010).

Mahjani M.G., Ehsani A., Jafarian M.. Synth. Met. 2010;160:1252. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2010.03.019.A. Ehsani, M. G. Mahjani, M. Jafarian, A. Naeemy, Electrochimica. Acta. 71, 128(2012).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M. G., Jafarian M., Naeemy A.. Electrochimica. Acta. 2012;71:128. 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.03.107.A.R. Feizbakhsh, A. Naeemy, A. Ehsani, A. Aghasi, I. Danaee, J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 59, 1086(2012).

Feizbakhsh A.R., Naeemy A., Ehsani A., Aghasi A., Danaee I.. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2012;59:1086. 10.1002/jccs.201100570.A. Ehsani, M.G. Mahjani, M. Jafarian, Synth. Met. 161, 1760(2011).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M.G., Jafarian M.. Synth. Met. 2011;161:1760. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2011.06.020.A. Ehsani, M. G. Mahjani, M. Jafarian, A. Naeemy, Progress in organic coating, 69, 510(2010).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M. G., Jafarian M., Naeemy A.. Progress in organic coating 2010;69:510. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2010.09.007.S. Radhakrishnan, A. Adhikari, DK. Awasti. Chem. Phys. Lett, 341, 518(2001).

Radhakrishnan S., Adhikari A., Awasti DK.. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001;341:518. 10.1016/S0009-2614(01)00547-4.S. Berchmans, H. Gomathi, GP. Rao. J. Electroanal. Chem, 394, 267(1995).

Berchmans S., Gomathi H., Rao GP.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1995;394:267. 10.1016/0022-0728(95)04099-A.R. Ojani, J.-B. Raoof, S. Fathi, Electrochim. Acta, 54, 2190(2009).

Ojani R., Raoof J.-B., Fathi S.. Electrochim. Acta 2009;54:2190. 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.10.023.F.D. Eramo, J.M. Marioli, A.A. Arevalo, L.E. Sereno, Electroanalysis, 11, 481(1999).

Eramo F.D., Marioli J.M., Arevalo A.A., Sereno L.E.. Electroanalysis 1999;11:481. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4109(199906)11:7<481::AID-ELAN481>3.0.CO;2-7.A.J. Bard, L.R Faulkner. Electrochemical Methods. Wiley, New York (2001).

Bard A.J., Faulkner L.R. Electrochemical Methods Wiley. New York: 2001.A. Ehsani, MG. Mahjani, M. Jafarian, Synth. Met. 162, 199(2012).

Ehsani A., Mahjani MG., Jafarian M.. Synth. Met. 2012;162:199. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2011.11.032.A. Ehsani, Prog. Org. Coat, 78, 133-139(2015).

Ehsani A.. Prog. Org. Coat 2015;78:133–139. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2014.09.015.A. Ehsani, MG. Mahjani, M. Bordbar, S. Adeli, J. Electroanal. Chem. 710, 29(2013).

Ehsani A., Mahjani MG., Bordbar M., Adeli S.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2013;710:29. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2013.01.008.A. Ehsani, M.G. Mahjani, M. Jafarian, Turk. J. Chem. 35, 1(2011).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M.G., Jafarian M.. J. Chem. 2011;35:1.A. Ehsani, M.G. Mahjani, S. Adeli, S. Moradkhani, Prog. Org. Coat. 77, 1674(2014).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M.G., Adeli S., Moradkhani S.. Prog. Org. Coat. 2014;77:1674. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2014.05.027.A. Ehsani, MG. Mahjani, R. Moshrefi, H. Mostaanzadeh, J. Shabani Shayeh, RSC. Adv. 4, 2231(2014).

Ehsani A., Mahjani MG., Moshrefi R., Mostaanzadeh H.. J. Shabani Shayeh, RSC. Adv. 2014;4:2231.A. Ehsani, M. Nasrollahzadeh, MG. Mahjani, R. Moshrefi, H. Mostaanzadeh, Ind. Eng. Chem. 20, 4363(2014).

Ehsani A., Nasrollahzadeh M., Mahjani MG., Moshrefi R., Mostaanzadeh H.. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014;20:4363. 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.01.045.A. Ehsani, M.G. Mahjani, M. Nasseri, M. Jafarian, Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 61, 146(2014).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M.G., Nasseri M., Jafarian M.. Methods Mater. 2014;61:146.A. Ehsani, B. Jaleh, M. Nasrollahzadeh, J. Power Sources. 257, 300(2014).

Ehsani A., Jaleh B., Nasrollahzadeh M.. J. Power Sources. 2014;257:300. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.02.010.A. Ehsani, S. Adeli, F. Babaei, H. Mostaanzadeh, M. Nasrollahzadeh, J. Electroanal. Chem, 713, 91(2014).

Ehsani A., Adeli S., Babaei F., Mostaanzadeh H., Nasrollahzadeh M.. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2014;713:91. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2013.12.003.S. Naghdi, B. Jaleh, A. Ehsani, Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 88, 722(2015).

Naghdi S., Jaleh B., Ehsani A.. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 2015;88:722. 10.1246/bcsj.20140402.A. Ehsani, R. Moshrefi, M. Ahmadi, Electrochemical Science and Technology, 6(1), 7(2015).

Ehsani A., Moshrefi R., Ahmadi M.. Electrochemical Science and Technology 2015;6(1):7.A. Ehsani, F. Babaei, H. Mostaanzadeh, J. of the Brazilian Chem. Soc., 26, 331(2015).

Ehsani A., Babaei F., Mostaanzadeh H.. J. of the Brazilian Chem. Soc. 2015;26:331.A. Ehsani, ,M G. Mahjani, F. Babaei, H. Mostaanzadeh, RSC Advances, 5, 30394(2015).

Ehsani A., Mahjani M G., Babaei F., Mostaanzadeh H.. RSC Advances 2015;5:30394. 10.1039/C5RA02297E.A. Ehsani, A. Vaziri-Rad, F. Babaei, H. Mohammad Shiri, Electrochim. Acta, 159, 140(2015).

Ehsani A., Vaziri-Rad A., Babaei F., Shiri H. Mohammad. Electrochim. Acta 2015;159:140. 10.1016/j.electacta.2015.01.204.